THE SYNCREATE PODCAST: EMPOWERING CREATIVITY

HOSTED BY MELINDA ROTHOUSE, PHD

WELCOME TO SYNCREATE, WHERE WE EXPLORE THE INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN CREATIVITY, PSYCHOLOGY, AND SPIRITUALITY. OUR GOAL IS TO DEMYSTIFY THE CREATIVE PROCESS, AND EXPAND THE BOUNDARIES OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE CREATIVE.

SUBSCRIBE / FOLLOW US ON SPOTIFY, APPLE PODCASTS, GOOGLE PODCASTS, AND YOUTUBE

HOSTED BY MELINDA ROTHOUSE, PHD

WELCOME TO SYNCREATE, WHERE WE EXPLORE THE INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN CREATIVITY, PSYCHOLOGY, AND SPIRITUALITY. OUR GOAL IS TO DEMYSTIFY THE CREATIVE PROCESS, AND EXPAND THE BOUNDARIES OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE CREATIVE.

SUBSCRIBE / FOLLOW US ON SPOTIFY, APPLE PODCASTS, GOOGLE PODCASTS, AND YOUTUBE

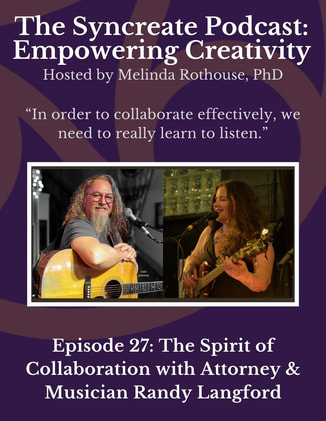

EPISODE 27: THE SPIRIT OF COLLABORATION

WITH ATTORNEY & MUSICIAN Randy Langford

LISTEN TO THE AUDIO EPISODE HERE:

WATCH THE FULL VIDEO VERSION HERE:

Collaboration is vital for getting things done, for innovation, and for solving complex problems. Sometimes we can go it alone, but most of the time, we must work collaboratively with others to achieve our professional, creative, and personal goals. But do we really understand collaboration, and what distinguishes it from coordination, cooperation, and even teamwork? According to our current guest, Randy Langford, collaboration involves people in community using dialogue or conversation to express their needs, and offering resources to support one another, for an agreed to or common purpose. It’s basically the opposite of competition, the way our system generally operates.

Randy is an Austin-based attorney, professor, and musician with a focus on collaboration and restorative justice. He worked as a criminal defense attorney before turning his attention to more collaborative legal practices. We discuss his journey from the ranches of southeast Texas, through law school and the criminal justice system, to championing collaboration through his law practice and teaching. Randy is also a prolific singer-songwriter, and he and Melinda have recently been collaborating on music and performance. We discuss our musical collaboration and share a couple of songs from our current collaborative show, Colors of Love.

For our Creativity Pro-Tip, reflect on how you collaborate in your creative, professional, and personal life. Try embracing the spirit of collaboration in asking for what you need, sharing resources, and supporting your collaborators toward a common purpose.

Credits: The Syncreate podcast is created and hosted by Melinda Rothouse, and produced at Record ATX studios with in collaboration Michael Osborne and 14th Street Studios in Austin, Texas. Syncreate logo design by Dreux Carpenter.

If you enjoy this episode and want to learn more about the creative process, you might also like our conversations in

Episode 9: Music and Psychology: "The Pocket" Experience with Dr. Jeff Mims

Episode 11: Leadership, Values, and Criminal Justice Reform with Attorney Dylan Hayre

Episode 14: Anatomy of a Song with Singer/Songwriter George McCormack

Episode 17: Creative Collaboration with Syncreate Podcast Producer Mike Osborne

At Syncreate, we're here to support your creative endeavors, so if you have an idea for a project or a new venture, please reach out to us for 1x1 coaching or join our Syncreate 2024 Coaching Group, starting in April. You can find more information on our website, syncreate.org, where you can also find all of our podcast episodes. Find and connect with us on YouTube, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram & TikTok under Syncreate, and we’re now on Patreon as well.

If you enjoy the show, please subscribe and leave us a review!

Randy is an Austin-based attorney, professor, and musician with a focus on collaboration and restorative justice. He worked as a criminal defense attorney before turning his attention to more collaborative legal practices. We discuss his journey from the ranches of southeast Texas, through law school and the criminal justice system, to championing collaboration through his law practice and teaching. Randy is also a prolific singer-songwriter, and he and Melinda have recently been collaborating on music and performance. We discuss our musical collaboration and share a couple of songs from our current collaborative show, Colors of Love.

For our Creativity Pro-Tip, reflect on how you collaborate in your creative, professional, and personal life. Try embracing the spirit of collaboration in asking for what you need, sharing resources, and supporting your collaborators toward a common purpose.

Credits: The Syncreate podcast is created and hosted by Melinda Rothouse, and produced at Record ATX studios with in collaboration Michael Osborne and 14th Street Studios in Austin, Texas. Syncreate logo design by Dreux Carpenter.

If you enjoy this episode and want to learn more about the creative process, you might also like our conversations in

Episode 9: Music and Psychology: "The Pocket" Experience with Dr. Jeff Mims

Episode 11: Leadership, Values, and Criminal Justice Reform with Attorney Dylan Hayre

Episode 14: Anatomy of a Song with Singer/Songwriter George McCormack

Episode 17: Creative Collaboration with Syncreate Podcast Producer Mike Osborne

At Syncreate, we're here to support your creative endeavors, so if you have an idea for a project or a new venture, please reach out to us for 1x1 coaching or join our Syncreate 2024 Coaching Group, starting in April. You can find more information on our website, syncreate.org, where you can also find all of our podcast episodes. Find and connect with us on YouTube, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram & TikTok under Syncreate, and we’re now on Patreon as well.

If you enjoy the show, please subscribe and leave us a review!

EPISODE-SPECIFIC HYPERLINKS

Randy Langford’s Law Website

Restorative Justice

Shamanacana, Randy’s Music Site

Randy’s YouTube Channel, including full videos of the songs from this Episode

Melinda Joy Music Website

Restorative Justice

Shamanacana, Randy’s Music Site

Randy’s YouTube Channel, including full videos of the songs from this Episode

Melinda Joy Music Website

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Melinda: Welcome to Syncreate, a show where we explore the intersections between creativity, psychology and spirituality. We believe everyone has the capacity to be creative, and our goal is to demystify the creative process while expanding the boundaries of what it means to be creative. I'm Melinda Rothouse, and I help individuals and organizations bring their creative dreams and visions to life.

So, my very special guest today is my dear friend, colleague, and collaborator Randy Langford.

Oklahoma born and Texas raised; in your former life, worked as a ranch hand and then later in life, went back to school, became an attorney with a focus on criminal defense and restorative justice. You're also a professor and a musician, and we collaborate together musically. We've just recently put together a show called Colors of Love, which we'll get into a little bit later in the show.

And so our focus today is on collaboration, which seems to me to be a really common thread in kind-of everything that you do. So I want to start with, you know, what is collaboration? Like, how do you define collaboration, and how do you teach it to students?

Randy: Well, that is a very good question because I think people have very different understandings of collaboration. And it does make a difference, our understanding of collaboration. So what I tell students, and in the classes I teach, that I'm not declaring what collaboration is. I tell them this will be our understanding of collaboration, during our course of study. And that understanding that we use is: people in community, using dialogue or conversation, to express their needs, and offer resources to support one another, for an agreed to or common purpose.

And you know, I think that pretty well covers any kind of interaction that people would want to have coming together for some endeavor, whether it be just dreaming up innovative ideas, or actually trying to accomplish some task, or something like that.

Melinda: Yeah, and I love that. When you first told me that definition--we were talking about it a while back--you know, it really struck me: both the openness and transparency of communication, and the idea of sharing resources. And I think we also talked about asking for what you need. And what really strikes me is that, how often we don't do that in our everyday lives.

You know, collaboration as you're defining it is kind of the antithesis of competition, which is often a way we go about things in our society. So I really loved that definition, and I've shared it with a lot of people since then. So when you teach collaboration, so you teach at St. Edward's University, here in Austin, and you teach several different classes. So, you know, what kind of stumbling blocks do people run into when entering into these kind of collaborations?

Randy: Well, you know, there are different approaches to teamwork, coming together in groups. And most of us have had plenty of experience with the other two primary approaches, which would be coordination and cooperation, which, you know, those two approaches, you can accomplish them with very little communication between people. You know, one is coordination [which] primarily can be understood as teamwork for the purpose of implementation.

You know, getting-from-here-to-there type thing, and do it in a way that is efficient and doesn't cause any kind of catastrophes. And then cooperation is, you know, people coming together, but everyone just focusing on their goal, you know, what they have to do. And so both coordination and cooperation require exploitation.

Melinda: Interesting.

Randy: It’s about exploiting resources from different sources, whatever they may be. Collaboration, on the other hand--I think this is why coordination and cooperation actually are maybe a little more comfortable for folks, because of what they entail--because what collaboration requires, rather than it being exploitive or exploitative, it is supportive. And so it's people offering resources rather than trying to exploit them. And, of course, if we're offering resources, we need to know what we're offering resources for.

So people have to become comfortable with expressing what they need within a collaboration, which requires communication. And it requires a particular approach to communication, one that is not demanding or persuasive, but an approach to communication that it is used for the intent of understanding one another. So the, you know, really the skill that we need to develop then, in order to collaborate effectively, is to be really good listeners. We need to really learn to listen.

Melinda: And I would imagine we also have to have some self-awareness to be able to communicate, and to listen and, you know, to share, to know what we have to offer to the situation and then be able to articulate what we need. And also something you said earlier, you know, in the examples of cooperation, you know, it's like you're kind of working together toward a common end. But the end goal is the thing. And it seems to me, at least in my experiences of collaboration, that it's as much about the people. And you mentioned in the beginning community, you know, it's as much about the people and the process, as it is about the final product.

Randy: Yeah. Whereas, you know, these other types of teamwork, coordination, cooperation, they usually have something they're focusing on, trying to get somewhere, right? But, you know, collaboration really is for the sake of collaboration. And what, you know, oftentimes we end up in places we never could have dreamed of before, because the whole does become greater than the sum of the parts.

Melinda: Yeah. Yeah. So this, where you are now, and you've had this long and interesting journey to get there, which includes restorative justice, which seems to me to be a collaborative form of working toward resolution when there's conflict. And so I'm curious if you would just share with us a little bit more about your journey, how you discovered restorative justice and you know, how you approach it, and how it can be used in the community, for those who may not be familiar.

Randy: Sure. Yeah. So 20 years or so ago when I first came to Austin, after, you know, leaving the life that you had mentioned earlier, I was going to college for the first time. I'd never gone to university studies or anything. And at that at the same time I was studying at the university, I was hired by some criminal defense lawyers, just to be their assistant. They wanted someone who had not been tainted by any other lawyer.

And so I fit the bill for them. You know, I could hardly spell law, much less, you know, do anything about it. And so they would take me; they were great. I mean, just amazing folks. And they would take me to all their continuing legal education seminars and stuff. And they took me to one that had a woman who was giving a presentation.

She happened to be the Director of Victim Services for the Travis County District Attorney's Office. And she told this unbelievable story about how she was a realtor, about to go out and show houses, and a guy in a ninja suit dropped through the ceiling of her bedroom while she was in the bathroom, went in there, assaulted her, and left her for dead. You know, I mean, it was really a miracle that she survived. And, of course, how could you ever feel safe anywhere if someone's dropping out of your ceiling in your home?

Melinda: The worst nightmare.

Randy: Yeah. You know, so she was, her life, she couldn't live really anymore. And she was, to the point, she was almost to that place where she didn't want to live anymore. And someone had told her about a retired Lutheran minister who was working in the TDC, in the corrections department for the state, who was doing this thing called restorative justice.

And she went to meet with him. He explained to her that you had to experience it, like he could talk to her about it all day long but she had to experience it. So she wanted to they had arrested her assailant, and she wanted to meet with him, because she couldn't imagine why anybody would do that to her. It's, he didn't know her. It was completely.

Melinda: Random.

Randy: Random thing. You know, it wasn't, they didn't rob her or anything, you know. And so he wouldn't meet with her. But they were able to find someone who had committed a similar offense who was. And so it was kind of a surrogate for her. And it was just that opportunity to have that conversation, and to really listen, for both people to listen to one another, that it was transformative for her.

It basically gave her her life back, and it was so impactful upon her that she decided that's what she wanted to do. So she began to really dive into restorative justice, and restorative practices and later on became the director of the--she even has a woman's prison named after her.

Melinda: Wow.

Randy: Up in Gatesville. So anyway, I saw her, at this, speaking at this CLE, and went up to her afterwards because I was attending St. Edward's University, where I was going at the time.

And in order to graduate, you had to write a capstone paper, which is kind of a thesis, and it was, it needed to be about some kind of social justice issue. And so I thought, man, this is like my ticket, right? Yeah, this is perfect right here. So I went up and spoke with her and I said, told her what my situation was, and she invited me to come to her office over at the DA's office.

And I did one day, and she had this giant cardboard box just full of videos, back then, VHS tapes. She had videotapes and books and articles, and everything in this box. And she sat down and we talked for a little bit and she said, “Well, here's what I suggest you do. Take this box that I put together for you and read and watch everything that's in there and then come back and let's talk again.”

So I did. I went back and I dove into it and came back and she said, “I want you to know that you might be one of the most well-informed people on restorative justice now that I've ever met, if you if you went through everything in that box.” She said, you know, and I told her I did. I said, “I read every paper and I watched every video.” And she says, “Well, then you have the knowledge about restorative justice, but you don't know what restorative justice is.” She said, “The way that happens is through your experiencing it.” And she said, “I'm sending you down the hall to my colleague,” who was the head of social services for the Travis County Sheriff's Office in the jail.

And she said “They are about to do a restorative justice pilot program in the jail; it’d be one of the first ones ever done in a county jail. And you're going to be their first volunteer to facilitate.” I said,”Okay. Thank you.” So I went down there and sure enough, that's how it started, and what my experience was, much like hers, was that, you know, I thought I was going in there to help all these folks who had fallen, you know, south of the law kind of thing.

And what ended up happening is, is it changed me. It transformed me. You know, I was the one who was really receiving this amazing gift, through them telling their stories, and their vulnerability. And it opened me up to tell my stories. And you know, stuff that I'd never told anyone. And that process was cathartic and healing.

Melinda: Yeah. Yeah. So for those maybe who've never experienced anything quite like this, and I have some limited knowledge about, you know, I've used some principles of restorative justice, in a context that I was involved with a while back, but essentially just kind of walk us through. You come into a room, you come into a situation with a group of stakeholders, and there has been some conflict or perhaps even a crime committed, right? And then you bring all these people together. And then what? What happens then?

Randy: So, yeah. So the kind of the conventional approach to justice, as we understand it, you know, identifies one person as an offender and one person as a victim. And all of the resources are focused on the offender. I mean, we spend millions upon millions upon millions of dollars, right? So, and nobody else is really concerned with it, other than the professionals who are making a living off that system.

So with restorative justice, it's a recognition that, you know, yes, there might be a person who took action that resulted in consequences that affected primarily one other person. But neither one of those people are living in a vacuum. And so the person who took the action, and oftentimes it's like that one moment when, you know, when your entire life is, you're known by a single act in a moment in time, kind of thing.

But it's a recognition that, you know, there were a lot of other people involved in that person's life that were responsible for things that might have brought them to that moment, as well as there's a responsibility to you on the part of the person or the persons who were directly impacted by it as to how they respond. They're responsible for that.

And so to use the term that you used, stakeholders come together without implying these titles on one another victim and offender, That's something that's has come about in the current system, that's an adversarial, retributive justice system that has kind of corrupted the process a little bit. But, and, you know, when we're talking about how folks did it from 3,000 years ago who, were from the indigenous peoples, where these processes came from and approaches, it would just be folks sitting in a circle telling stories, and everyone would have an opportunity to tell their story about whatever the event was and how it impacted them.

And there was no judgment; there was no judge, and there was no judgment. And together, they collectively and collaboratively decided how they were going to address this challenge; what needed to be done to restore everybody to wholeness or as much wholeness as could be possible. And that's in summary.

Melinda: Yes, and wholeness being the goal, right? Not punishment, not retribution, but the collective wholeness. Everybody, together, getting to that place.

Randy: Yeah, Because, you know, back in the day when folks lived in tribes and clans, you know, if every time there was someone offended, someone else did something that they didn't like or they had some kind of conflict. There was some judgment made and, you know, maybe someone was expelled from the tribe or executed or something like that. Well, because we human beings tend to butt heads pretty regularly, you know? Pretty soon there's no one left, right? And it's then that tribe will be taken over by the next tribe. Somebody by the next tribe.

So they had to figure out a way to address humanity. Just being human beings, you know, having conflict from time to time. Differences of opinion, maybe doing things that caused real impactful harm to one another. How are we going to address that in a way that results in the tribe being stronger?

Melinda: Yes. And maintain the integrity of the community.

Randy: Yeah. So that's how those processes developed over the millennia.

Melinda: Great. So is there an example or that you might share of where you, you know, witnessed or participated in this process and sort-of what was the result of it or what was the outcome?

Randy: Yeah, I've have a lot of stories. I mean, you walk away sometimes, you think how was that possible? Or, I never would have seen that coming, kind of thing. One that I'd tell, and it's kind of funny, but really amazing. I was working, doing a program, a restorative justice programs, about 14 week program in a prison at Uvalde.

And it was, you know, I mean, there were folks in there for murder and sexual assault and things like that. And so in this one group of with this group of men there, I was working primarily just with the men there. And one of them was a Hispanic guy just tattooed from head to toe.

And you could tell that he had he had done some time. And we were sitting in a circle. There were probably about 10 of us. And, you know, from week to week, he would sit there. And sometimes you have folks who just want to get other cells come in, you know? And he would he would just be sitting there, you know, and we would go around the circle and we use it as a talking piece.

And when the talking piece would come to him, to he would just pass it on. Which you can do. And he never said a word for 14 weeks. Never said a word. And at the end of the 14 weeks, we're about to have our last circle, and the talking piece went around to him. And he held at this time and he said, “I killed a man to get in here. And then his brother killed my sister. And I've been waiting for the day when I'm released from prison so I could go kill him. But after sitting in this circle, I decided I'm just going to let that go.”

Wow.

Yeah. So I'm going to stop the cycle of it right now. And then he passed it on.

Melinda: Amazing.

Randy: And all he been doing is just listening to these stories. You know, he had never said a word.

Melinda: Right. Right. But by and I think this is a testament to kind of empathy and compassion. You know, the more we are able to listen, and really hear other people's stories, and be able to kind of put ourselves in their shoes, or imagine things from beyond our own perspective, our own need for revenge or retribution or whatever. And see like how our actions might actually impact other people.

And that violence just begets violence, right? And then you start to go, maybe there's another way.

Randy: Yeah. And you also, one thing that that was really just eye opening for me is, when you hear some people's stories and you know that they're in there for murder or a serious assault or something. And I would sit there and be thinking, “How did you get through life and only kill one person”? What your story, what you have gone through, I'm talking about from being a young child, you know, things like one person, you know, saw his father murder his mother, and then the family would refuse to let him talk about it. He could not talk about it with anyone. And that's what he grew up with. And it's like, so how did you restrain yourself from only, you know, hurting one person like that?

So, and that's part of, like, the community, right? Like, there's more people responsible here than this one person who did this one thing.

Melinda: Right. These things don't just come out of. Nowhere, right?

Randy: Right.

Melinda: Yeah, exactly. Well, I want to touch on one other aspect of your legal work as it relates to collaboration. And then I want to talk about our musical collaborations as well. So, you know, currently in your legal practice, my understanding is you focus more on drawing up agreements, contracts, and you use a process called Dynamic Agreement for people that are entering into any sort of partnership or something like that.

And it is also a collaborative approach, right, to forming a partnership or whatever it might be, as opposed to the more traditional way that contracts are drawn, which is very sort-of litigious. Right. So tell us about that. If you are working with clients who are coming together to, you know, create something, a partnership, whatever it might be, what's the process that you take them through?

Randy: So yeah, so I immediately out of law school, because I had been working for criminal defense attorneys, I decided I was going to take this restorative justice stuff, you know, that I had picked up along the way, and I was going to find some way to infuse it into the criminal justice system and, you know, change the world.

Which I gave it a good solid seven, almost eight years. And it became apparent to me that I wasn't going to change the system. The system was changing me. And that if I was going to use this approach, this more collaborative restorative approach, I was going to have to extricate myself from the system.

And it took me a while to, kind-of, it's not an easy thing to do in the law, because the law is dependent on the system, right? So I began to work, and I spent about two years, and burned up all my savings, trying to figure out a way to incorporate these processes and techniques and the philosophy of restorative justice, and how to bring it into another realm like business. And what I came up with, what was this Dynamic Agreement. And Dynamic Agreement, what it does is, if you were to pick up any, just a conventional contract, it would not take--you wouldn't have to read through very many paragraphs--that it would become clear probably initially, that it was very one sided. And that it immediately started posturing the parties as future litigants.

They were going to be adversaries. It was clear that it was set up that planning on them being adversaries.

Melinda: Right. And you brought this to my attention. Even something as simple as a lease agreement is set up in that adversarial way, if you really sit down and look at it.

Randy: Yeah. So what Dynamic Agreement does is, it doesn't do that. The processes involved in the collaborative co-creation of the agreement go into the memorialization of that agreement in the document, always posturing people as collaborators. Us. We. Our. And everything is mutual and reciprocal, so that it's respectful of the needs and concerns and desires of the participants.

And I don't even refer to the folks as parties, because parties is litigious term, right. They're participants in an collaborative co-creation of agreement. And it's also, it accepts that and recognizes that, if there is one thing that is not a certainty in the lives of human beings is change. And usually what causes agreements to go south, is that some change occurs and rather than see that change as an opportunity to just make adjustments, and to together figure out a way how to address a challenge or a change, it results in people blaming one another, which brings in the lawyers, which leads to litigation, which dissolves the agreement. The agreement’s terminated at that time, and usually the relationship, if there was one.

Melinda: Yes. And how many times have we heard this happening? People go in with the best intentions, right? Whether it's a marriage, or a business partnership, or whatever. And then something happens and everybody walks away, kind-of broken hearted.

Randy: Yeah. So in conventional agreements, contracts, almost the entirety of the attention is on the transactional aspects. Terms and conditions, right? With and, you know, the parties are just two blank lines that you write in two names some place.

Melinda: Right.

Randy: But with a Dynamic Agreement, at least as much attention is placed on the relationship between the participants as the terms of the agreement. So it starts off with a foundation statement, where the two participants come together and say, “You know what? We might want to talk about values. We might want to talk about, I don't know, the world we want to live in.” And if we can't, you know, because if we can't, if we can't come together and at least find values that are mutually acceptable, maybe we shouldn't be entering into this agreement together.

Melinda: Great. Good point. And, you know, when I talk to coaching clients, for example, one of the first things we often talk about is values, which people I think have a sense of their values, but they haven't always articulated them explicitly. And we start to understand what our values are often when they are violated.

Randy: Right.

Melinda: Right. So to spend some time thinking about that in advance, like what do we want to create together? What are our shared values? How do we want to enter into this?

Randy: Yeah. And what I've discovered in that process is, also, how do we understand these values? Yes, because you and I might sit here and say, “Well, you know, Melinda, respect is really an important value to me.” And you say, “Well, respect is really important to me, Randy, also.” And then we start talking about respect. And it's like we're talking about two things, right?

Melinda: Exactly, yeah.

Randy: So it's that conversation. It's having that dialogue, that conversation where we're really listening to one another and not trying to sell one another on something, or persuade one another. We're really listening. And then I can decide, well, we might have different understandings of respect, but your understanding is acceptable to me. Right. I might not join you in it, but it's acceptable. And then we can start coming together and collaborating on this agreement. When we do that, because ordinarily in the in the conventional approach, all of that comes out way down the road. And then it's catastrophic.

Melinda: Right. And it's too late.

Randy: Yeah, it's too late. You know, because it's going to come out at some point in time. Those values are going to become, they're going to, there's going to be a situation that presents itself where we're both going to claim that this is not in alignment with a value that I have. But we're going to be so vested, and invested, in whatever the endeavor is, that oftentimes it just dissolves everything, including the relationship.

Melinda: Yes. Yeah. And so within this process of Dynamic Agreement, my understanding is it also includes kind of some language, some thinking, some talking about, “Okay, when disagreements or conflicts almost inevitably arise, how are we going to deal with them? How are we going to address them?”

Randy: Yeah. And it requires a, maybe a different understanding of conflict. Because ordinarily, you know, if you're anything thing like me, you know, conflict was generally regarded as something to avoid. And if you did engage conflict, there was punishment for it. And it had a negative, negative connotation. And I found that if we can just shift our understanding of conflict so that rather than it be something that is punitive and something to be avoided, and we simply regard it as diversity of perspective. Conflict is nothing more than diversity of perspective. That's it. So now we have a whole different approach to if we see it that way. No one's trying to do us wrong. People are just simply expressing their perspective.

And in the in the context of collaboration, that's a strength and not a weakness. Having all these different perspectives. This is a resource to use. And so when we do have these challenges or changes, you know, conflict that arises within the context of an endeavor related to an agreement, first off, we don't try to avoid it. There's nothing to be punished for. And if we have agreed upon the process we're going to use to address those things, it's just a regular part and we already know what's going to happen. We're not surprised by it. We know ahead of time this is going to occur.

Melinda: Not afraid of it.

Randy: Okay. Let's bring our process in now. And let's apply the process. And then this shift moves from focusing on personalities to process. Because whatever the challenge is, is out there. It's not, the challenge isn't me.

Melinda: And it's not personal.

Randy: Yeah. The challenge is out there, and we come together as collaborative co-creators to address the challenge, using the process.

Melinda: Right. So we're a team here, trying to figure this out, rather than we're against each other.

Randy: It's just another thing for us to collaborate on.

Melinda: Yeah, It's great. Awesome. Well, I want to make sure we have some time to talk about our musical collaborations. So, like so many of us in Austin, we have our work that we do in the world, and we are also creatives and musicians. So, you know, you and I have known each other for a few years. We were introduced by a mutual friend a while back, and then we kind of reconnected more recently over music.

And I came out to one of your shows, and then we started playing some shows together, and started learning each other's songs. And then we were talking about, you know, booking shows and putting something together, and kind-of had this idea, along with Alisa, your significant other, and two of our other collaborators, George McCormack, who we featured in Episode 14, and Jason Hendrix. And the five of us kind-of got together and just started brainstorming like, you know, we're all out here, like playing these separate gigs, and doing our thing, and sometimes playing together and sometimes not.

But what if we brought all of our resources together collaboratively and created a whole show, a whole performance? And one of the things I love [about] this is, you know, we just started talking about this couple of months ago, right? And we set ourselves a completely arbitrary deadline: Let's do it in February. Let's, like, make it Valentine's themed. And so we've managed to produce this whole show, which we had a big performance last Saturday, February 10th.

And what really amazed me about this collaboration was how beautifully and organically it came together, not knowing in advance how it was going to work. There was no one person directing this show saying like, “This is how it's going to be. This is my vision.” We all just brought what we brought to the table, and it was this emergent process. So I don't know, what's your perspective on that collaboration?

Randy: I'm as amazed with it as you are. You know, it was, it's really beautiful. Because, I mean, even when we began to come together, like we didn't have a vision for anything, we just came together and we just started talking. We just, and what I, what I recognized and really appreciated, is that nobody identified with any idea that they put out there.

It would be like, what do you think about this? And if they didn't work for somebody, okay, well, you know, what do you think about this? You know, and that and even when we started playing music together, I know particularly with my music, that obviously I played it a particular way when I was just playing it solo.

But when we brought in everyone else, it changed my song. But it changed it in a way, like it was organic, and I changed with it. It felt like the song no longer belonged to me, kind of thing, you know? It was no longer my song. It was our song, that we were coming together and collaborating to present. And that, I was really like it. Just thinking about it makes me smile.

Melinda: I know. And that's one of the things I love about musical collaborations specifically because, you know, as a sort of singer/songwriter and bass player, I often come up with a bass line and a melody, and then I need the other people to come in and fill it out and I never know exactly what that's going to look like.

And depending on who I'm playing with, and the instrumentation, and their particular style, you know, each person brings something different to the song. And it's always better than if I had just said, okay, you play this, you play this, you play this. You know, it's like there's this kind of synergy that happens. That's so beautiful.

Randy: Yeah. And you know, that's it. And, you know, even you know, we practiced for our production, Colors of Love, and you know, obviously it was pretty clunky at first, you know. We were trying to feel our way, and it started coming together and started coming together. But I'm telling you, when we finally had our performance that's when you could tell that we were a collaborative body. We were collaborative co-creators, in that moment right there, you know, it was all it all came together the time that we had spent just talking, sharing, listening, you know, trying stuff out, stuff like that. Boom, It came together.

Melinda: It really did. Yeah. So I want to talk about a couple of your songs, as our guest today, that were a part of that performance. And we'll be sharing a couple of those as part of the episode. So the first one I kind of want to talk about is a song of yours called Central Park, and there's a story that you tell usually before we play it, about how that song came about. So tell us about that.

Randy: Yeah. So after I graduated from law school, I needed to rest my brain a little bit, and I think I'd had just taken the bar exam, I believe, maybe. But anyway, I went to New York and I had never been to New York before and had a little travel guitar. And I was staying at a hotel that wasn't too far from Central Park, and I was just, it was so dramatic that it caught my attention immediately, that where I was staying, it was loud. And people were bumping into one another, and it was busy, and taxis and cars going all over the place. I walked across the street and walked, like through a portal, into Central Park, and it was tranquility. And there were birds, and there's dogs running around chasing balls and, you know, people holding hands and everything. And it's like, you stick your head out over here and it’s [chaotic], and over where, you go over here and it's nice.

So I walked into Central Park, and I found a big gray rock that I didn't know was in Central Park, but there are a lot of them. And I climbed up on the top of this rock, and I sat up there with a little notepad, and I just started writing down what I saw. And all of these people in different kinds of relationships, relationships with their dogs, their pets, with friends, lovers, you know, people are just enjoying nature, you know, the plants and everything.

And the sounds you could hear. And so I just started scribbling those down. And then I got to thinking about how those relationships change over time, you know. And sometimes they dissolve and sometimes that, you know, people might pass away or move away, or do these kinds of things. And, kind-of the chorus is kind-of a lamentation of that. But it's, you know, that's part of life and part of new relationships, as that happens. And so that's how the song came to be.

Melinda: Yeah, great. And it's such a fun one to play. Well, we'll include it here with the with the podcast.

[Song Plays: Central Park from Colors of Love]

Melinda: And then the other one, and these two songs are kind-of, you know, very different energy; another one that we really enjoy playing is called It's Time. It's very upbeat and kind-of one of those audience participation songs. So, tell us about that one.

Randy: Yeah, It's Time. Actually, it was inspired by a lovely song that you're familiar with as well. And I really was stricken by the chord progression and the melody in that song. And so I just started messing around with that, just playing it, you know, I wasn't thinking about any lyrics or anything, or whether or not a song was even going to come of it.

And all of a sudden it was just this, it has, you know, that kind of tribal beat and groove to it and everything. And so, you know, this idea of a shaman or a shaman-like person coming in to someone's life who had, you know, powers over them kind-of thing and, and a little story arose out of that, you know, someone being stricken by a person like that and really being drawn to them.

And then that person kind-of using their powers, you know, in that relationship to extract things and exploit things from another person. And finally, the person was really smitten wakes up and says, you know, it's time to get you out, put you out of my misery! [Laughter]

Melinda: Yes! It's such a great one. Yeah. So we'll hear that one as well from our Colors of Love Show.

[Song Plays: It’s Time from The Colors of Love]

Melinda: Really, what that provokes for me is around the creative process, right? Just these two songs that we've been talking about. One was inspired by, you know, this trip to New York and going into the park and just seeing everyday life playing out. And then this other one, you know, you're trying to figure out the chords to an existing song, and then all of a sudden, this whole story just arises. You know, it just really illustrates to me how we can find inspiration in, you know, everyday things, in taking inspiration from other people's work, and other people's art. And then sometimes something just shows up.

Randy: Yeah, you know, I know it sounds, I guess maybe even a little pretentious, but it is my experience; I really don't take credit for writing any songs.

Melinda: You're a very prolific songwriter, by the way.

Randy: And they just come to me from wherever they come. Like, and it's not me sitting there and, you know, scratching out. It just doesn't work like that for me. They come when they come, and when they come, they sometimes they just come all at once. It's a done deal you, know.

And some of them come in bits and pieces, you know, along the way. I wouldn't even be thinking about them, and then something happens. Or I'd often, more times than I can count, it'll come to me in my sleep. I'll wake up with it, and I'll go as fast as I can to try to write it down before I forget about it, you know.

Melinda: That happened to me with this song recently, and I felt like it was such a gift, you know? And there's so much to be said, I think, for just being an open vessel for what wants to arrive. You know, we have these faculties, and these sense perceptions, and this consciousness. And, you know, sometimes we just think it's about us, it's about me. But really, you know, here we are; we're tuned into this whole world around us. And that becomes a source of inspiration. Sometimes we don't even know how.

Randy: Yeah, there was a song that we played; I think I played it at your place one time. We had a little gathering out there, was a song that the lyrics say, “Sometimes words never come.” And where that came from was I had been playing a chord progression until I was sick of listening to myself play it. And I had an old, beat-up guitar, and I threw it across the room onto the bed, out of frustration, that I couldn't think of the first line. And as soon as I did that, every lyric to that song came to me.

Melinda: That's incredible.

Randy: It just fell out of my head as I did that. It was just like, how is this possible? You know, this is [Laughter].

Melinda: Yeah, which reminds me, you know, the phrase like “Sometimes breakdown, leads to breakthrough.” We get so frustrated, and we're not getting anywhere, and we're stuck, and then throw the guitar across the room. And there it is. You know, you never know what's going to spark something.

So that's great. Well, thank you so much, Randy. I've loved our conversation on collaboration. And if people want to find out more about you, both your legal work and your music, how can they find you?

Randy: If they'll Google “my lawyer friend,” it’ll usually bring up my law practice website right there, and they want to see some stuff about what's going on musically, go to shamanacana dot com.

Melinda: And I just have to ask, what is Shamanacana? That's kind of your brand.

Randy: I was I was told one time, someone asked me what how I would describe my music. And I said, “You know, that's a good question. I don't really know. It's a little of this, a little of that.” And he says “Well I listened to that, and I'd call it Shamanacana.” And I said, “That's it, right there.” It's perfect.

Melinda: Yeah. It's perfect. It's so great. Alright. Well, I usually end each episode with kind -a Creativity Pro-Tip that people can sort of run with try out on their own. So given our theme of collaboration today, I want to, you know, circle back to that and really encourage people to think about what collaborations you might be involved with, whether that's at work, whether that's in your family, you know, your sort-of extracurricular life, your creative life, and how you might be able to bring more of that spirit of collaboration in, in terms of open communication, asking for what you need, sharing resources.

I think, I don't know, for me, somehow that really crystallized what collaboration is and what it can be. Because, you know, as we've talked about with our collaboration, when you really open heartedly do those things, there's a magic that happens and a synergy that happens that is just quite remarkable.

Randy: Yeah, we get out of our own way when we do that.

Melinda: Exactly. Yeah.

At Syncreate, we're here to support your creative endeavors. So if you have an idea for a project and you'd like our help, please reach out to us for 1x1 coaching or join our Syncreate 2024 coaching group, which is starting in April, just a couple months away. You can find more information on our website syncreate.org, and you can also find all of our podcast episodes there.

We’re also on social media and YouTube. We're on LinkedIn, Facebook, Insta, TikTok. So find us under Syncreate, connect with us. We're also on Patreon. If you are enjoying the show and would like to contribute. And love for you to subscribe and leave us a review, if you feel so inspired. And we are recording today at Record ATX Studios in Austin and the podcast is produced in collaboration with Mike Osborne at 14th Street Studios.

So Randy, thank you so much.

Randy: Thank you.

Melinda: Yeah. And thank you to all of you listening and watching and we'll see you next time.

So, my very special guest today is my dear friend, colleague, and collaborator Randy Langford.

Oklahoma born and Texas raised; in your former life, worked as a ranch hand and then later in life, went back to school, became an attorney with a focus on criminal defense and restorative justice. You're also a professor and a musician, and we collaborate together musically. We've just recently put together a show called Colors of Love, which we'll get into a little bit later in the show.

And so our focus today is on collaboration, which seems to me to be a really common thread in kind-of everything that you do. So I want to start with, you know, what is collaboration? Like, how do you define collaboration, and how do you teach it to students?

Randy: Well, that is a very good question because I think people have very different understandings of collaboration. And it does make a difference, our understanding of collaboration. So what I tell students, and in the classes I teach, that I'm not declaring what collaboration is. I tell them this will be our understanding of collaboration, during our course of study. And that understanding that we use is: people in community, using dialogue or conversation, to express their needs, and offer resources to support one another, for an agreed to or common purpose.

And you know, I think that pretty well covers any kind of interaction that people would want to have coming together for some endeavor, whether it be just dreaming up innovative ideas, or actually trying to accomplish some task, or something like that.

Melinda: Yeah, and I love that. When you first told me that definition--we were talking about it a while back--you know, it really struck me: both the openness and transparency of communication, and the idea of sharing resources. And I think we also talked about asking for what you need. And what really strikes me is that, how often we don't do that in our everyday lives.

You know, collaboration as you're defining it is kind of the antithesis of competition, which is often a way we go about things in our society. So I really loved that definition, and I've shared it with a lot of people since then. So when you teach collaboration, so you teach at St. Edward's University, here in Austin, and you teach several different classes. So, you know, what kind of stumbling blocks do people run into when entering into these kind of collaborations?

Randy: Well, you know, there are different approaches to teamwork, coming together in groups. And most of us have had plenty of experience with the other two primary approaches, which would be coordination and cooperation, which, you know, those two approaches, you can accomplish them with very little communication between people. You know, one is coordination [which] primarily can be understood as teamwork for the purpose of implementation.

You know, getting-from-here-to-there type thing, and do it in a way that is efficient and doesn't cause any kind of catastrophes. And then cooperation is, you know, people coming together, but everyone just focusing on their goal, you know, what they have to do. And so both coordination and cooperation require exploitation.

Melinda: Interesting.

Randy: It’s about exploiting resources from different sources, whatever they may be. Collaboration, on the other hand--I think this is why coordination and cooperation actually are maybe a little more comfortable for folks, because of what they entail--because what collaboration requires, rather than it being exploitive or exploitative, it is supportive. And so it's people offering resources rather than trying to exploit them. And, of course, if we're offering resources, we need to know what we're offering resources for.

So people have to become comfortable with expressing what they need within a collaboration, which requires communication. And it requires a particular approach to communication, one that is not demanding or persuasive, but an approach to communication that it is used for the intent of understanding one another. So the, you know, really the skill that we need to develop then, in order to collaborate effectively, is to be really good listeners. We need to really learn to listen.

Melinda: And I would imagine we also have to have some self-awareness to be able to communicate, and to listen and, you know, to share, to know what we have to offer to the situation and then be able to articulate what we need. And also something you said earlier, you know, in the examples of cooperation, you know, it's like you're kind of working together toward a common end. But the end goal is the thing. And it seems to me, at least in my experiences of collaboration, that it's as much about the people. And you mentioned in the beginning community, you know, it's as much about the people and the process, as it is about the final product.

Randy: Yeah. Whereas, you know, these other types of teamwork, coordination, cooperation, they usually have something they're focusing on, trying to get somewhere, right? But, you know, collaboration really is for the sake of collaboration. And what, you know, oftentimes we end up in places we never could have dreamed of before, because the whole does become greater than the sum of the parts.

Melinda: Yeah. Yeah. So this, where you are now, and you've had this long and interesting journey to get there, which includes restorative justice, which seems to me to be a collaborative form of working toward resolution when there's conflict. And so I'm curious if you would just share with us a little bit more about your journey, how you discovered restorative justice and you know, how you approach it, and how it can be used in the community, for those who may not be familiar.

Randy: Sure. Yeah. So 20 years or so ago when I first came to Austin, after, you know, leaving the life that you had mentioned earlier, I was going to college for the first time. I'd never gone to university studies or anything. And at that at the same time I was studying at the university, I was hired by some criminal defense lawyers, just to be their assistant. They wanted someone who had not been tainted by any other lawyer.

And so I fit the bill for them. You know, I could hardly spell law, much less, you know, do anything about it. And so they would take me; they were great. I mean, just amazing folks. And they would take me to all their continuing legal education seminars and stuff. And they took me to one that had a woman who was giving a presentation.

She happened to be the Director of Victim Services for the Travis County District Attorney's Office. And she told this unbelievable story about how she was a realtor, about to go out and show houses, and a guy in a ninja suit dropped through the ceiling of her bedroom while she was in the bathroom, went in there, assaulted her, and left her for dead. You know, I mean, it was really a miracle that she survived. And, of course, how could you ever feel safe anywhere if someone's dropping out of your ceiling in your home?

Melinda: The worst nightmare.

Randy: Yeah. You know, so she was, her life, she couldn't live really anymore. And she was, to the point, she was almost to that place where she didn't want to live anymore. And someone had told her about a retired Lutheran minister who was working in the TDC, in the corrections department for the state, who was doing this thing called restorative justice.

And she went to meet with him. He explained to her that you had to experience it, like he could talk to her about it all day long but she had to experience it. So she wanted to they had arrested her assailant, and she wanted to meet with him, because she couldn't imagine why anybody would do that to her. It's, he didn't know her. It was completely.

Melinda: Random.

Randy: Random thing. You know, it wasn't, they didn't rob her or anything, you know. And so he wouldn't meet with her. But they were able to find someone who had committed a similar offense who was. And so it was kind of a surrogate for her. And it was just that opportunity to have that conversation, and to really listen, for both people to listen to one another, that it was transformative for her.

It basically gave her her life back, and it was so impactful upon her that she decided that's what she wanted to do. So she began to really dive into restorative justice, and restorative practices and later on became the director of the--she even has a woman's prison named after her.

Melinda: Wow.

Randy: Up in Gatesville. So anyway, I saw her, at this, speaking at this CLE, and went up to her afterwards because I was attending St. Edward's University, where I was going at the time.

And in order to graduate, you had to write a capstone paper, which is kind of a thesis, and it was, it needed to be about some kind of social justice issue. And so I thought, man, this is like my ticket, right? Yeah, this is perfect right here. So I went up and spoke with her and I said, told her what my situation was, and she invited me to come to her office over at the DA's office.

And I did one day, and she had this giant cardboard box just full of videos, back then, VHS tapes. She had videotapes and books and articles, and everything in this box. And she sat down and we talked for a little bit and she said, “Well, here's what I suggest you do. Take this box that I put together for you and read and watch everything that's in there and then come back and let's talk again.”

So I did. I went back and I dove into it and came back and she said, “I want you to know that you might be one of the most well-informed people on restorative justice now that I've ever met, if you if you went through everything in that box.” She said, you know, and I told her I did. I said, “I read every paper and I watched every video.” And she says, “Well, then you have the knowledge about restorative justice, but you don't know what restorative justice is.” She said, “The way that happens is through your experiencing it.” And she said, “I'm sending you down the hall to my colleague,” who was the head of social services for the Travis County Sheriff's Office in the jail.

And she said “They are about to do a restorative justice pilot program in the jail; it’d be one of the first ones ever done in a county jail. And you're going to be their first volunteer to facilitate.” I said,”Okay. Thank you.” So I went down there and sure enough, that's how it started, and what my experience was, much like hers, was that, you know, I thought I was going in there to help all these folks who had fallen, you know, south of the law kind of thing.

And what ended up happening is, is it changed me. It transformed me. You know, I was the one who was really receiving this amazing gift, through them telling their stories, and their vulnerability. And it opened me up to tell my stories. And you know, stuff that I'd never told anyone. And that process was cathartic and healing.

Melinda: Yeah. Yeah. So for those maybe who've never experienced anything quite like this, and I have some limited knowledge about, you know, I've used some principles of restorative justice, in a context that I was involved with a while back, but essentially just kind of walk us through. You come into a room, you come into a situation with a group of stakeholders, and there has been some conflict or perhaps even a crime committed, right? And then you bring all these people together. And then what? What happens then?

Randy: So, yeah. So the kind of the conventional approach to justice, as we understand it, you know, identifies one person as an offender and one person as a victim. And all of the resources are focused on the offender. I mean, we spend millions upon millions upon millions of dollars, right? So, and nobody else is really concerned with it, other than the professionals who are making a living off that system.

So with restorative justice, it's a recognition that, you know, yes, there might be a person who took action that resulted in consequences that affected primarily one other person. But neither one of those people are living in a vacuum. And so the person who took the action, and oftentimes it's like that one moment when, you know, when your entire life is, you're known by a single act in a moment in time, kind of thing.

But it's a recognition that, you know, there were a lot of other people involved in that person's life that were responsible for things that might have brought them to that moment, as well as there's a responsibility to you on the part of the person or the persons who were directly impacted by it as to how they respond. They're responsible for that.

And so to use the term that you used, stakeholders come together without implying these titles on one another victim and offender, That's something that's has come about in the current system, that's an adversarial, retributive justice system that has kind of corrupted the process a little bit. But, and, you know, when we're talking about how folks did it from 3,000 years ago who, were from the indigenous peoples, where these processes came from and approaches, it would just be folks sitting in a circle telling stories, and everyone would have an opportunity to tell their story about whatever the event was and how it impacted them.

And there was no judgment; there was no judge, and there was no judgment. And together, they collectively and collaboratively decided how they were going to address this challenge; what needed to be done to restore everybody to wholeness or as much wholeness as could be possible. And that's in summary.

Melinda: Yes, and wholeness being the goal, right? Not punishment, not retribution, but the collective wholeness. Everybody, together, getting to that place.

Randy: Yeah, Because, you know, back in the day when folks lived in tribes and clans, you know, if every time there was someone offended, someone else did something that they didn't like or they had some kind of conflict. There was some judgment made and, you know, maybe someone was expelled from the tribe or executed or something like that. Well, because we human beings tend to butt heads pretty regularly, you know? Pretty soon there's no one left, right? And it's then that tribe will be taken over by the next tribe. Somebody by the next tribe.

So they had to figure out a way to address humanity. Just being human beings, you know, having conflict from time to time. Differences of opinion, maybe doing things that caused real impactful harm to one another. How are we going to address that in a way that results in the tribe being stronger?

Melinda: Yes. And maintain the integrity of the community.

Randy: Yeah. So that's how those processes developed over the millennia.

Melinda: Great. So is there an example or that you might share of where you, you know, witnessed or participated in this process and sort-of what was the result of it or what was the outcome?

Randy: Yeah, I've have a lot of stories. I mean, you walk away sometimes, you think how was that possible? Or, I never would have seen that coming, kind of thing. One that I'd tell, and it's kind of funny, but really amazing. I was working, doing a program, a restorative justice programs, about 14 week program in a prison at Uvalde.

And it was, you know, I mean, there were folks in there for murder and sexual assault and things like that. And so in this one group of with this group of men there, I was working primarily just with the men there. And one of them was a Hispanic guy just tattooed from head to toe.

And you could tell that he had he had done some time. And we were sitting in a circle. There were probably about 10 of us. And, you know, from week to week, he would sit there. And sometimes you have folks who just want to get other cells come in, you know? And he would he would just be sitting there, you know, and we would go around the circle and we use it as a talking piece.

And when the talking piece would come to him, to he would just pass it on. Which you can do. And he never said a word for 14 weeks. Never said a word. And at the end of the 14 weeks, we're about to have our last circle, and the talking piece went around to him. And he held at this time and he said, “I killed a man to get in here. And then his brother killed my sister. And I've been waiting for the day when I'm released from prison so I could go kill him. But after sitting in this circle, I decided I'm just going to let that go.”

Wow.

Yeah. So I'm going to stop the cycle of it right now. And then he passed it on.

Melinda: Amazing.

Randy: And all he been doing is just listening to these stories. You know, he had never said a word.

Melinda: Right. Right. But by and I think this is a testament to kind of empathy and compassion. You know, the more we are able to listen, and really hear other people's stories, and be able to kind of put ourselves in their shoes, or imagine things from beyond our own perspective, our own need for revenge or retribution or whatever. And see like how our actions might actually impact other people.

And that violence just begets violence, right? And then you start to go, maybe there's another way.

Randy: Yeah. And you also, one thing that that was really just eye opening for me is, when you hear some people's stories and you know that they're in there for murder or a serious assault or something. And I would sit there and be thinking, “How did you get through life and only kill one person”? What your story, what you have gone through, I'm talking about from being a young child, you know, things like one person, you know, saw his father murder his mother, and then the family would refuse to let him talk about it. He could not talk about it with anyone. And that's what he grew up with. And it's like, so how did you restrain yourself from only, you know, hurting one person like that?

So, and that's part of, like, the community, right? Like, there's more people responsible here than this one person who did this one thing.

Melinda: Right. These things don't just come out of. Nowhere, right?

Randy: Right.

Melinda: Yeah, exactly. Well, I want to touch on one other aspect of your legal work as it relates to collaboration. And then I want to talk about our musical collaborations as well. So, you know, currently in your legal practice, my understanding is you focus more on drawing up agreements, contracts, and you use a process called Dynamic Agreement for people that are entering into any sort of partnership or something like that.

And it is also a collaborative approach, right, to forming a partnership or whatever it might be, as opposed to the more traditional way that contracts are drawn, which is very sort-of litigious. Right. So tell us about that. If you are working with clients who are coming together to, you know, create something, a partnership, whatever it might be, what's the process that you take them through?

Randy: So yeah, so I immediately out of law school, because I had been working for criminal defense attorneys, I decided I was going to take this restorative justice stuff, you know, that I had picked up along the way, and I was going to find some way to infuse it into the criminal justice system and, you know, change the world.

Which I gave it a good solid seven, almost eight years. And it became apparent to me that I wasn't going to change the system. The system was changing me. And that if I was going to use this approach, this more collaborative restorative approach, I was going to have to extricate myself from the system.

And it took me a while to, kind-of, it's not an easy thing to do in the law, because the law is dependent on the system, right? So I began to work, and I spent about two years, and burned up all my savings, trying to figure out a way to incorporate these processes and techniques and the philosophy of restorative justice, and how to bring it into another realm like business. And what I came up with, what was this Dynamic Agreement. And Dynamic Agreement, what it does is, if you were to pick up any, just a conventional contract, it would not take--you wouldn't have to read through very many paragraphs--that it would become clear probably initially, that it was very one sided. And that it immediately started posturing the parties as future litigants.

They were going to be adversaries. It was clear that it was set up that planning on them being adversaries.

Melinda: Right. And you brought this to my attention. Even something as simple as a lease agreement is set up in that adversarial way, if you really sit down and look at it.

Randy: Yeah. So what Dynamic Agreement does is, it doesn't do that. The processes involved in the collaborative co-creation of the agreement go into the memorialization of that agreement in the document, always posturing people as collaborators. Us. We. Our. And everything is mutual and reciprocal, so that it's respectful of the needs and concerns and desires of the participants.

And I don't even refer to the folks as parties, because parties is litigious term, right. They're participants in an collaborative co-creation of agreement. And it's also, it accepts that and recognizes that, if there is one thing that is not a certainty in the lives of human beings is change. And usually what causes agreements to go south, is that some change occurs and rather than see that change as an opportunity to just make adjustments, and to together figure out a way how to address a challenge or a change, it results in people blaming one another, which brings in the lawyers, which leads to litigation, which dissolves the agreement. The agreement’s terminated at that time, and usually the relationship, if there was one.

Melinda: Yes. And how many times have we heard this happening? People go in with the best intentions, right? Whether it's a marriage, or a business partnership, or whatever. And then something happens and everybody walks away, kind-of broken hearted.

Randy: Yeah. So in conventional agreements, contracts, almost the entirety of the attention is on the transactional aspects. Terms and conditions, right? With and, you know, the parties are just two blank lines that you write in two names some place.

Melinda: Right.

Randy: But with a Dynamic Agreement, at least as much attention is placed on the relationship between the participants as the terms of the agreement. So it starts off with a foundation statement, where the two participants come together and say, “You know what? We might want to talk about values. We might want to talk about, I don't know, the world we want to live in.” And if we can't, you know, because if we can't, if we can't come together and at least find values that are mutually acceptable, maybe we shouldn't be entering into this agreement together.

Melinda: Great. Good point. And, you know, when I talk to coaching clients, for example, one of the first things we often talk about is values, which people I think have a sense of their values, but they haven't always articulated them explicitly. And we start to understand what our values are often when they are violated.

Randy: Right.

Melinda: Right. So to spend some time thinking about that in advance, like what do we want to create together? What are our shared values? How do we want to enter into this?

Randy: Yeah. And what I've discovered in that process is, also, how do we understand these values? Yes, because you and I might sit here and say, “Well, you know, Melinda, respect is really an important value to me.” And you say, “Well, respect is really important to me, Randy, also.” And then we start talking about respect. And it's like we're talking about two things, right?

Melinda: Exactly, yeah.

Randy: So it's that conversation. It's having that dialogue, that conversation where we're really listening to one another and not trying to sell one another on something, or persuade one another. We're really listening. And then I can decide, well, we might have different understandings of respect, but your understanding is acceptable to me. Right. I might not join you in it, but it's acceptable. And then we can start coming together and collaborating on this agreement. When we do that, because ordinarily in the in the conventional approach, all of that comes out way down the road. And then it's catastrophic.

Melinda: Right. And it's too late.

Randy: Yeah, it's too late. You know, because it's going to come out at some point in time. Those values are going to become, they're going to, there's going to be a situation that presents itself where we're both going to claim that this is not in alignment with a value that I have. But we're going to be so vested, and invested, in whatever the endeavor is, that oftentimes it just dissolves everything, including the relationship.

Melinda: Yes. Yeah. And so within this process of Dynamic Agreement, my understanding is it also includes kind of some language, some thinking, some talking about, “Okay, when disagreements or conflicts almost inevitably arise, how are we going to deal with them? How are we going to address them?”

Randy: Yeah. And it requires a, maybe a different understanding of conflict. Because ordinarily, you know, if you're anything thing like me, you know, conflict was generally regarded as something to avoid. And if you did engage conflict, there was punishment for it. And it had a negative, negative connotation. And I found that if we can just shift our understanding of conflict so that rather than it be something that is punitive and something to be avoided, and we simply regard it as diversity of perspective. Conflict is nothing more than diversity of perspective. That's it. So now we have a whole different approach to if we see it that way. No one's trying to do us wrong. People are just simply expressing their perspective.

And in the in the context of collaboration, that's a strength and not a weakness. Having all these different perspectives. This is a resource to use. And so when we do have these challenges or changes, you know, conflict that arises within the context of an endeavor related to an agreement, first off, we don't try to avoid it. There's nothing to be punished for. And if we have agreed upon the process we're going to use to address those things, it's just a regular part and we already know what's going to happen. We're not surprised by it. We know ahead of time this is going to occur.

Melinda: Not afraid of it.

Randy: Okay. Let's bring our process in now. And let's apply the process. And then this shift moves from focusing on personalities to process. Because whatever the challenge is, is out there. It's not, the challenge isn't me.

Melinda: And it's not personal.

Randy: Yeah. The challenge is out there, and we come together as collaborative co-creators to address the challenge, using the process.

Melinda: Right. So we're a team here, trying to figure this out, rather than we're against each other.

Randy: It's just another thing for us to collaborate on.

Melinda: Yeah, It's great. Awesome. Well, I want to make sure we have some time to talk about our musical collaborations. So, like so many of us in Austin, we have our work that we do in the world, and we are also creatives and musicians. So, you know, you and I have known each other for a few years. We were introduced by a mutual friend a while back, and then we kind of reconnected more recently over music.

And I came out to one of your shows, and then we started playing some shows together, and started learning each other's songs. And then we were talking about, you know, booking shows and putting something together, and kind-of had this idea, along with Alisa, your significant other, and two of our other collaborators, George McCormack, who we featured in Episode 14, and Jason Hendrix. And the five of us kind-of got together and just started brainstorming like, you know, we're all out here, like playing these separate gigs, and doing our thing, and sometimes playing together and sometimes not.

But what if we brought all of our resources together collaboratively and created a whole show, a whole performance? And one of the things I love [about] this is, you know, we just started talking about this couple of months ago, right? And we set ourselves a completely arbitrary deadline: Let's do it in February. Let's, like, make it Valentine's themed. And so we've managed to produce this whole show, which we had a big performance last Saturday, February 10th.

And what really amazed me about this collaboration was how beautifully and organically it came together, not knowing in advance how it was going to work. There was no one person directing this show saying like, “This is how it's going to be. This is my vision.” We all just brought what we brought to the table, and it was this emergent process. So I don't know, what's your perspective on that collaboration?

Randy: I'm as amazed with it as you are. You know, it was, it's really beautiful. Because, I mean, even when we began to come together, like we didn't have a vision for anything, we just came together and we just started talking. We just, and what I, what I recognized and really appreciated, is that nobody identified with any idea that they put out there.

It would be like, what do you think about this? And if they didn't work for somebody, okay, well, you know, what do you think about this? You know, and that and even when we started playing music together, I know particularly with my music, that obviously I played it a particular way when I was just playing it solo.

But when we brought in everyone else, it changed my song. But it changed it in a way, like it was organic, and I changed with it. It felt like the song no longer belonged to me, kind of thing, you know? It was no longer my song. It was our song, that we were coming together and collaborating to present. And that, I was really like it. Just thinking about it makes me smile.

Melinda: I know. And that's one of the things I love about musical collaborations specifically because, you know, as a sort of singer/songwriter and bass player, I often come up with a bass line and a melody, and then I need the other people to come in and fill it out and I never know exactly what that's going to look like.

And depending on who I'm playing with, and the instrumentation, and their particular style, you know, each person brings something different to the song. And it's always better than if I had just said, okay, you play this, you play this, you play this. You know, it's like there's this kind of synergy that happens. That's so beautiful.

Randy: Yeah. And you know, that's it. And, you know, even you know, we practiced for our production, Colors of Love, and you know, obviously it was pretty clunky at first, you know. We were trying to feel our way, and it started coming together and started coming together. But I'm telling you, when we finally had our performance that's when you could tell that we were a collaborative body. We were collaborative co-creators, in that moment right there, you know, it was all it all came together the time that we had spent just talking, sharing, listening, you know, trying stuff out, stuff like that. Boom, It came together.